WHEN Salima leapt over the puddle the radio completed Morris Nyunyusa's third and last note to usher in the six o'clock news. In the fullness of her poetry, Salima defined the laws of gravity, barely floating above the puddle and he thought her duck's gait held her on her own among beauties where beauty was given great pleasure. She belonged to a family of wasps, Mayasa, all legs and on the noon bosom under a colourful rag, her brassiere was a superfluous item.

The poet had watched verses pass through the Imam's mouth with anticipation for the last line of the surat - after prayers spread out - for he knew that was the time Salima walked from her stall, past the mosque, to the last house before she cut into an alley to a room in the backyard of the shop. At the phrase, By the white forenoon and the brooding night! the poet crawled over the jute mats to retrieve his sandals from the cupboard by the entrance and walked out. Just then the coffee seller appeared in his usual fashion from the shadow of the mango tree with a clink of cups. The poet indicated an order and flattened his spine against the pillars oblivious to verses inside.

He sipped without hurry but with a feeling of boundless anxiety. This was the day, he figured, that he had found at last the courage to face her if only to hear the dazzle of her armpits. His wild gaze remained fixed on the nocturnal corner of this unbearable moment of his unremarkable life and that morning as in all his mornings he had made the same vow to throw away the silence of her cat's paws' footfalls, vanishing beyond the Indian's shop, and as in all evenings after prayers he came back to the same anticipation until it became a habit. Beginning with the morning vows before the blur of activities of day and then the evening prayers. Thus he teased and tormented himself, and even found a kind of pleasure doing so.

Although at the time he didn't think of it as a moral problem he had, not without some reservations, broken the issue with the Imam in a round-the-pot way about what possible evils that can interfere with one's prayers. The Imam replied with no apparent logic:

"Speak no ill of any man, good or evil, if you are wise; for you make the evil man your enemy and turn the good man into an evil one."

"From your lips to ears of believers." The poet agreed, and inflamed his conscience for the morning, filling himself with the optimist's doubt: was he there to worship or to bow for a beauty? Although it was also true that he began saying his prayers quite a while ago, long before the inopportune appearance of Salima Mayasa's walk through the street. But come the next evening he was back at his station gazing at the same corner, waiting to the same flutter of the same trail of the same woman, and did not think much of the warning. Admittedly, a feeling of infinite loathing over himself had begun to overcome him and the only outlet to follow his agitation to it logical conclusion. But only he knew what that entailed, for Salima not unlike all women of the town it was said that her loin had the hunger of satiate entire ward of male prisoners.

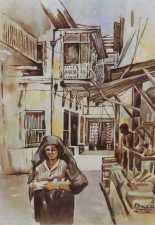

If one sat under the shade of the mosque as the poet Saadani did every evening after Maghrib prayers, it was possible to see as if in a tunnel, across the length of the yard the market place, and on one side the Indian's shop. At last, the poet looked fleetingly at the first light pouring out of Indian Kanji's shop. Kanji himself was supervising last piles of garish clothes being carried in by his man servant, a slovenly ragamuffin who normally roamed the crowds in the market and when clouds of his sanity returned, his eyes became frozen melancholically, especially when he talked about his previous life, about his wife who it was said had a bad spell cast on him to revenge his cheating. The poet Saadani did not know for sure but another theory was that symptoms of that insanity could only be explained by juju especially unleashed in the coast since the demons of the poet's town did not shout or speak Arabic with the fluency of a born-speaker. And all those who knew the ragamuffin since childhood knew that he never spoke Arabic apart from a few prayers spaced between the break of the fast and the return of the pilgrims. The Indian's light was the light Salima was best illuminated in.

But now the poet's head was swimming with the evening trail of her wrap's steaming message: Beyond that reef of sand, recalling a house and a lady dismount where the winds crossed the still extant traces of Salima's sweat. He stood up and calmly dove into undulating lights in the puddle and swam toward the shop. Kanji's contraband of untaxed cigarettes and the ragamuffin's underwear floated past and the imam's distress call went unheeded because the currents had thrown him on the side of the street where the Indian's shop was and in the ensuing melee her wrap had unfastened and the trail grew into a ceremony so that he felt it build like bubbles. She turned back with measured indifference, her breath into his breath, the quest broken and he had the audacity of a lance corporal's lust and nailed her right there on the spot. The drum entered its theme song, the bridal chamber, and fed out seeking in his own fever the same voice, was the feather on her brow an angel or atonement or a mystery?

Salima, again, led the horn barely above water, her hand once more wiping hair off her face. He was also surprised by the fluidity of her performance, the boneless dance of the waist as she took him, high above water, and without misgivings, rotated him, then squeezed and before she landed him on his head, he had the lucidity to remember a theory popular at the time that no man ever lasted two minutes inside Salima Mayasa without satisfaction, a refund at hand on falsification of the theory.

The poet still sipped his coffee, from the same station, looking at the same shop and the same ragamuffin, when Salima Mayasa disappeared beyond the light. His illusions shattered.

Before his timely death, the poet Saadani had given me this scene when he was explaining the meaning of Umar Khayyam's Ruba-iyyat: "If hand should give of the pith of the wheat a loaf, and of wine a two-maunder jug, of sheep a thigh, with a little sweetheart seated in desolation, a pleasure it is that is not the attainment of any sultan." The quatrain which, according to the poet Saadani, Edward Fitzgerald freely translated and distorted its meaning. When I asked him to explain he replied with one of his characteristic enigmas. "I marvel so dainty a waist could bear. The weight of jewels that glittered there."

That left me no wiser.